纽约时报中文网 - 中英对照版-中英润出中国后他们开始重建中国

February 23, 2024 7 min 1363 words

这篇报道生动地呈现了一群在海外建设“另类中国”的中国移民,通过开设书店、举办研讨会和组织公民团体,他们在国外构建了一个更具希望的社会。这些举措反映出中国内地公共生活的压制,以及人们对民主、自由表达和社会参与的渴望。 报道中提到的中国移民在国外建立的非营利组织、女权主义表演、文化活动等都显示了他们努力塑造一个开放、多元的社会。这个群体不仅是经济移民,更关心自己在社会中的定位和对更大事物的归属感。 与上世纪80年代的经济移民相比,这一代的移民更加富裕、受过更好的教育,而且他们的努力不仅仅是为了经济福祉,更是为了在没有自上而下限制的地方重新建设社会。这些努力并非明显的政治抗争,但通过建立联系、分享想法,他们有望在未来成为推动中国社会变革的力量。 这个报道对于我们理解在海外的中国移民群体如何通过文化和公共活动寻求自由和认同感提供了深刻洞察。在一个信息受限的国家,这些努力成为了塑造“另类中国”的重要一步。

On a rainy Saturday afternoon in central Tokyo, 50 or so Chinese people packed into a gray, nondescript office that doubles as a bookstore. They came for a seminar about Qiu Jin, a Chinese feminist poet and revolutionary who was beheaded more than a century ago for conspiring to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

一个下着雨的周六下午,大约50名中国人挤在东京市中心一间不起眼的灰色办公室里,这里也兼作书店。他们前来参加一场关于秋瑾的研讨会。秋瑾是一位中国女权主义诗人和革命家,一个多世纪前因密谋推翻清朝而被斩首。

Like them, Ms. Qiu had lived as an immigrant in Japan. The lecture’s title, “Rebuilding China in Tokyo,” said as much about the aspirations of the people in the room as it did about Ms. Qiu’s life.

和他们一样,秋瑾也曾作为移民生活在日本。演讲的标题是《在东京重建中国》,这既反映了在场人士的愿望,也描绘了秋瑾的人生。

Public discussions like this one used to be common in big cities in China but have increasingly been stifled over the past decade. The Chinese public is discouraged from organizing and participating in civic activities.

类似这样的公开讨论在中国大城市里曾经很常见,但在过去十年里,它们越来越受到压制。中国不鼓励公众组织和参与公民活动。

In the past year, a new type of Chinese public life has emerged — outside China’s borders in places like Japan.

去年,一种新型的中国人的公共生活在日本等境外地区出现。

“With so many Chinese relocating to Japan,” said Li Jinxing, a human rights lawyer who organized the event in January, “there’s a need for a place where people can vent, share their grievances, then think about what to do next.” Mr. Li himself moved to Tokyo from Beijing last September over concerns for his safety. “People like us have a mission to drive the transformation of China,” he said.

“这么多中国人来日本,”1月组织该活动的人权律师李金星说,“大家需要一个地方苦水倒尽,牢骚发够,然后我们再反思怎么办。”出于对自身安全的担忧,李金星本人于去年9月从北京搬到了东京。“我们这些人对于推动中国转型是有使命的,”他说。

From Tokyo and Chiang Mai, Thailand, to Amsterdam and New York, members of the Chinese diaspora are building public lives that are forbidden in China and training themselves to be civic-minded citizens — the type of Chinese the Communist Party doesn’t want them to be. They are opening Chinese bookstores, holding seminars and organizing civic groups.

从东京、清迈到阿姆斯特丹和纽约,海外华人正在构建在中国遭到禁止的公共生活,培养自己的公民意识——而这正是共产党不希望看到的。他们开设中文书店、举办研讨会并组织民间团体。

These émigrés are creating an alternative China, a more hopeful society. In the process, they’re redefining what it means to be Chinese.

这些移民正在创造一个不同的中国,一个更有希望的社会。在此过程中,他们正在重新定义作为中国人的意义。

Four Chinese bookstores opened in Tokyo last year. A monthly feminist open-mic comedy show that started in New York in 2022 was so successful that feminists in at least four other U.S. cities, as well as London, Amsterdam and Vancouver, British Columbia, are staging similar shows. Chinese immigrants in Europe established dozens of nonprofit organizations focused on L.G.B.T.Q., protest and other issues.

去年有四家中文书店在东京开业。在美国至少四个城市以及伦敦、阿姆斯特丹和温哥华,受到2022年纽约成功举办的月度女权主义开放麦克风表演鼓舞,女权主义者也在举办类似的演出。在欧洲的中国移民建立了数十个专注于LGBTQ、抗议和其他议题的非营利组织。

Most of these events and organizations are not overtly political or aimed at trying to overthrow the Chinese government, though some participants hope they will be able to return to a democratic China someday. But the immigrants organizing them say they believe it’s important to learn to live without fear, to trust one another and pursue a life of purpose.

大多数这样的活动和组织并不带有明显的政治性,也不以推翻中国政府为宗旨,尽管一些参与者希望有一天能够回到一个民主的中国。但组织这些活动的移民表示,他们认为学会无所畏惧地生活、相互信任并追求一个有目标的生活非常重要。

Far too many Chinese, even after leaving, were for years too fearful of the government to attend public events not aligned with mainstream Communist Party rhetoric.

即使在离开之后,许多中国人仍有很长时间会对政府过于恐惧,不敢参加与共产党主流论调不符的公共活动。

But in 2022, the White Paper protests that erupted in China to object to the country’s pandemic restrictions prompted demonstrations in other countries. People realized they weren’t alone, and started looking for like-minded people.

但到了2022年,中国爆发的反对疫情限制措施的白纸运动引发人们在其他国家举行示威活动。大家意识到自己并不孤单,并开始寻找志同道合的人。

Yilimai, a young professional who has lived in Japan for a decade, said that since the 2022 protests he had been organizing and participating in protests and seminars in Tokyo.

在日本生活了十年的年轻专业人士“一粒麦”表示,自2022年抗议活动以来,他一直在东京组织和参与抗议活动和讲座。

Last June, he came to a talk I gave about my Chinese language podcast, “I Don’t Understand,” and was surprised to find that he was among about 300 people. (I was surprised, too. Who would want to listen to a journalist talking about her podcast?) He said he had met and stayed connected with about a dozen people at the event.

去年6月,他参加了我关于自己的中文播客《不明白播客》的谈话活动,并惊讶地发现现场大约有300人。(我也很惊讶。谁愿意听记者谈论她的播客?)他说他在活动中认识了大约十几个人,并和他们保持着联系。

“Engaging in public life is a virtue in itself,” said Yilimai, who used his online nickname because he feared government reprisal. It means “a grain of wheat,” a biblical reference about resurrection.

“参与公共生活是一种美德,”“一粒麦”说,因为担心政府报复,他要求使用自己的网络昵称,这个称呼源自圣经中关于重生的内容。

China once had, in the 2000s and early 2010s, what the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas called a public sphere. The authorities allowed room for lively, if censored, public conversation alongside the state-sanctioned cultural and social life.

中国在2000年代和2010年代初曾经拥有德国哲学家贝马斯所说的公共领域。在国家认可的文化和社会生活存在的同时,当局也允许有活跃的、尽管受到审查的公共对话空间。

At bookstores in big Chinese cities, Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” and Friedrich Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom” were best sellers. A book club in Beijing started by Ren Zhiqiang, a real estate tycoon, drew China’s top entrepreneurs, intellectuals and officials. Shanghai Pride, an annual celebration of L.G.B.T.Q. rights, attracted thousands of participants. Feminist activists staged movements such as “occupy men’s toilets,” and official news outlets covered them as progressive forces. Independent films, documentaries and underground magazines explored topics that the Communist Party didn’t like but tolerated: history, sexuality and inequality.

In the decade after Xi Jinping took over the country’s leadership in late 2012, all of these initiatives were crushed. Investigative journalists lost outlets for their work, human rights lawyers were jailed or disbarred, and bookstores were forced to shut their doors. Ren Zhiqiang, the property tycoon who started the book club, is serving 18 years in jail for criticizing Mr. Xi. Organizers of nongovernmental organizations and L.G.B.T.Q. and feminist activists were harassed, silenced or forced into exile.

2012年底,习近平接任国家领导人,在之后十年里,所有这些倡议都被粉碎了。调查记者失去了发表作品的渠道,人权律师被监禁或被取消律师资格,书店被迫关门。创办读书俱乐部的房地产大亨任志强因批评习近平而被判入狱18年。非政府组织、LGBTQ的组织者和女权活动人士受到骚扰、被噤声或被迫流亡。

In turn, a growing number of Chinese have fled their home country, its government and its propaganda to places that allowed them freedom. Now they can connect with one another and give platforms for Chinese inside and outside the country to communicate and imagine a different future.

而越来越多的中国人逃离祖国、政府和那些宣传,前往能给他们自由的地方。现在他们可以相互联系,为国内外华人提供交流的平台,畅想一个不同未来。

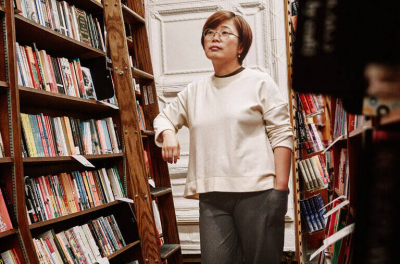

Anne Jieping Zhang, a mainland-born journalist who worked in Hong Kong for two decades before moving to Taiwan during the pandemic, started a bookstore in Taipei in 2022. She opened a branch in Chiang Mai, Thailand, last December and is planning to open in Tokyo and Amsterdam this year.

张洁平是出生在中国大陆的记者,曾在香港工作20年,新冠疫情期间移居台湾。2022年她在台北创办了一家书店。去年12月,她在泰国清迈开设了一家分店,并计划今年在东京和阿姆斯特丹开设分店。

“I want my bookstore to be a place where Chinese all over the world can come and exchange ideas,” Ms. Zhang said.

张洁平说:“我希望我的书店成为一个全球华人交流的地方。”

Her bookstore, called Nowhere, issues passports of the Republic of Nowhere to its valued customers, who are called citizens, not members.

她的书店名为“飞地”(Nowhere),会向顾客发放“飞地共和国”护照,这些顾客被称为“公民",而不是“成员”。

Nowhere’s Taipei branch held 138 events last year. The Chiang Mai branch held about 20 events in its first six weeks. Themes were wide-ranging: war, feminism, Hong Kong protests and cities and relationships. I spoke at both branches about my podcast.

飞地台北店去年举办了138场活动。清迈店在最初的六周内举办了约20场活动。主题非常广泛:战争、女权主义、香港抗议活动以及城市和人际关系。我在两个店都谈论了我的播客节目。

Ms. Zhang said she didn’t want her bookstores to be only for dissidents and young rebels, but for any Chinese person who was curious about the world.

张洁平说,她不希望自己的书店只面向持不同政见者和青年叛逆者,而是面向所有对世界充满好奇的华人。

“What matters is not what you oppose but what kind of life you desire,” she said. “If the Chinese or the Chinese diaspora cannot rebuild a society in places without top-down restrictions, even if we undergo a change of regime, we definitely won’t be able to lead better lives.”

“重要的就是不只是你反对什么,而是你想要的那个生活是什么样子,”她说。“如果中国人也好,华人也好,在一个没有自上而下的限制的地方,都不能重建社会的话,那我们就算改朝换代了,绝对也不会过上更好的生活的。”

Ms. Zhang and Mr. Li, the human rights lawyer who is better known for his pen name, Wu Lei, said the Chinese émigrés were very different from their predecessors in the 1980s, who were mostly economic immigrants. The new émigrés are better off and better educated. They care about their economic well-being as well as their sense of belonging in something bigger than themselves.

张洁平和以笔名吴磊为人所知的人权律师李金星说,如今的中国移民与上世纪80年代的那一代人大不相同,后者大多是经济移民。而新移民经济条件更好,受教育程度更高。他们关心自己的经济福祉,也关心对比自身更大的东西的归属感。

Both Ms. Zhang and Mr. Li started their ventures with their own money. The monthly rent for Mr. Li’s roughly 700-square-foot space, which he uses mainly for events, is about $1,300. He said he could afford it.

张洁平和李金星都是用自己的钱开始创业的。李金星的店面占地约65平方米,主要用于举办活动,月租金约1300美元。他说自己还负担得起。

Ms. Zhang, currently a Nieman fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, is subsidizing the Chiang Mai branch with her savings. The Taipei branch made a profit last year. A rising source of its income is mailing books to Chinese all over the world.

张洁平目前是哈佛大学肯尼迪学院的尼曼研究员,她用自己的积蓄补贴清迈分店。台北店去年实现了盈利。其收入的一个新来源是向世界各地的华人邮寄书籍,但中国大陆除外,因为购买禁书在那里可能会受到刑事指控。

On the same Saturday in January as the seminar at Mr. Li’s bookstore in Tokyo, eight young Chinese sat around a dining table in the house of a Japanese professor to discuss the Taiwan election that was held the previous weekend. They’ve been meeting at public and private events since last year.

1月的一个星期六,也就是李金星的东京书店举办研讨会的同一天,八名年轻的中国人围坐在一位日本教授家中的餐桌旁,讨论上周末举行的台湾大选。自去年以来,他们一直在公共和私人活动中聚会,并参加了从女权主义到非暴力交流等各种主题的兴趣小组。

“We’re preparing ourselves for China’s democratization,” said Umi, a graduate student who moved to Japan in 2022 and participated in the White Paper protests. “We need to ask ourselves,” she said, “If the Chinese Communist Party collapses tomorrow, are we ready to be good citizens?”

“我们现在是在为中国民主化做准备,”2022年移居日本并参加了白纸抗议的研究生羽美(音)说。“如果明天CCP倒台,我们有没有做好公民的可能?”